The Pulse (P)

What is a pulse?

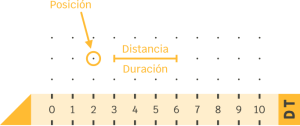

A pulse is a specific location on the timeline. It is the basic position element of the temporal dimension. The pulses mark the beginning and the end of the sounds, and therefore the rhythm of the melodies.

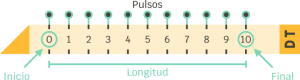

The length of the segment determines the number of pulses we can choose for our composition.

The same pulse can be identified in three different ways: by absolute numbering, by pulse segment numbering or by modular numbering. Each numbering has a different function.

ABSOLUTE NUMBERING

The absolute numbering allows us to place the pulses precisely within the timeline of the composition. In the Nuzic app, these absolute pulses (Pa) cannot be edited, nor can they be used to create sequences. They serve only to situate us in time.

SEGMENT PULSE NUMBERING

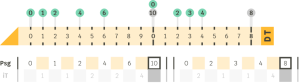

When we have several segments within the same composition, we can identify the pulses more easily using a numbering that is neither absolute nor modular, but is closely linked to the concept of segment.

This numbering resets the pulse counter to zero with each new segment. In addition to placing ourselves temporally within the segment, we can use this segment pulse (Psg) to create succesions.

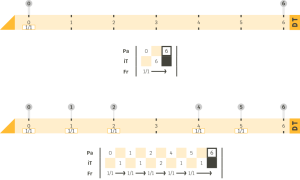

In the following example, we have a segment with a length of 10 pulsations. We have chosen pulses 0, 1, 2, 4 and 6 to place sounds in them.

As they are numbered from 0, the number of the last pulse equals the length of the segment. This last pulse cannot be selected and therefore does not sound. It is used to mark the end of the last pulsation.

MODULAR NUMBERING

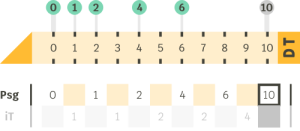

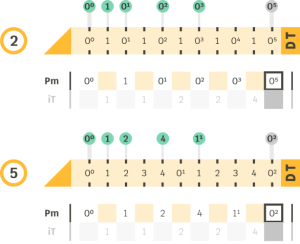

When working withbars, we can identify the pulses more easily using modular numbering. . Each modular pulse corresponds to a segment pulse and an absolute pulse with the same position but different numbering.

This modular numbering resets the pulse counter to zero with each new bar. In addition, to differentiate the pulses from each other, we indicate in which bar they are located (in bar 0, 1, 3, 8…). In mathematical terms, the numbering we use for these modular pulses (Pm) contains a main number (base), which locates the pulse within the bar, and another smaller number (exponent), which locates it within the succesion of bars.

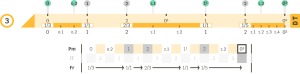

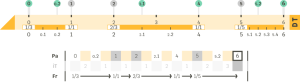

In the following examples we apply a bar of 2 and a bar of 5:

When using temporal fractions we generate new fractional pulses from the application of a fraction. The position and numbering of these pulses is different from that of the pulses that are not fraccional.

In the case of simple fractions, we use a decimal numbering to differentiate and place the new pulses on the timeline. On the other hand, in the case of complex fractions, the new pulses (called neopulses) maintain an integer numbering, whose location on the timeline is different from that of the absolute pulses.

In the specific case of applying a punctual fraction, we have to define some structural pulses to indicate the beginning and end of each fraction. The selected pulses can be chosen for our succesion or only have a structural function.

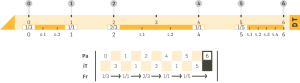

For example, in a segment of 6 pulses, in addition to pulse 0 and pulse 6 (the first and the last), we choose pulses 1, 2, 4 and 5 as structural pulses and apply the following fractioning: fraction ⅓ from pulse 0 to 1, fraction ⅔ from pulse 2 to 4, and fraction ⅕ from pulse 5 to 6. The intervals where we do not apply fractioning are kept at 1/1 by default.

|

Once the fractioning structure has been defined, we can choose the pulses for our succesion (marked in green). The structural pulses that we do not want to choose (marked in gray) must be kept in the table, although we can mute themwhile working on the sound dimension.

If we also apply a bar, we can see how the numbering of the pulses combines modular numbering with fractional numbering: